www.MuslimsInBritain.org

|

3. Islam’s

Place in the World and in Britain

3.1 Islam in the World

3.2 Principle Factions

3.2.1 Shi’a

3.2.2 Sunni

3.2.3 Deobandis and Bareilvis

3.2.4 Sunni Arab Movements

3.2.5 ‘Wahabbis’

3.2.6 Abul A’ala Maudoodi

3.2.7 Sunni

3.2.8 Sunni

3.3 Muslim Groups in Britain and in London

3.3.1 Muslims in Britain

3.3.2 Muslims in London

3.1 Islam in the World

The heartland of Islam is Arabia and Palestine. Muhammad Islam

spread over several centuries, westwards to cover North Africa and much of

Spain, northwards to much of Central Europe and southern Russia,

eastwards to include Indonesia and large parts of south-east China, and

southwards to southern Africa. The

twenty largest Muslim-majority countries are listed below.

The twenty largest Muslim minorities in non-Muslim countries are listed below, Britain being 20th on the list. The Muslim population of Britain has been estimated by the official UK Census at 1.6 million in 2001. Figures in this and the preceding table are taken from “The World Factbook” published by the US Central Intelligence Agency, and, for consistency, have not been amended e.g. with more accurate information about the UK, since corresponding changes in the other countries are not known.

3.2 Principle

Factions

90% of Muslims worldwide are Sunni, and about 10% are Shi’a. Other factions are subdivisions of these. Whereas definitions of Sunni and Shi’a are mutually exclusive, for most Muslims subdivisions below this level are informal and non-exclusive. 3.2.1 Shi’a

Shi-ism is concentrated in Iran and eastern Iraq, with very small pockets scattered between Iran and India, across Pakistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, plus some of the Emirates in the Gulf. Both Sunni and Shia traditions cover a wide spectrum of cultural practices

and degrees of religious commitment. Shi’as differ from

Sunnis over the leadership of the Muslim community following the

demise of the Prophet 3.2.2 Sunni

Sunnis believe the three and the fourth, Ali, as well, to be

Prophet’s Principle Sunni Divisions

3.2.3

Deobandis and Bareilvis

3.2.4

Sunni Arab Movements

3.2.5

‘Wahabbis’

3.2.6

Abul A’ala Maudoodi

3.2.7

Salafi

3.2.3 Deobandis

and Bareilvis

In India, Sunni religious scholarship polarised between Deoband Madressah and Bareili Madressah. Both maintained orthodox practices, but the former emphasised adherence to dogma whereas the latter became much more charismatic. Deoband followers, Deobandis, instituted Tabligh Jamaat, a practice of sending small groups of men from masjid to masjid spending a few days staying at each one, and preaching according to a rigid formula that enables any moderately educated person to convey the essentials of Islam without worrying about straying into scholarly ground. The Tablighi movement is worldwide and has been particularly effective at establishing religious consciousness, mosques and madressas around Britain. Nevertheless the largest communities of Muslims in Britain are from areas of Punjab and Kashmir where the Bareilvi charismatic Sufi traditions are strongest. Both groups, indeed every Sunni faction, describe themselves as “Ahl-as-Sunnah wa’l Jama’at” i.e. exclusive adherents of the true Sunnah, and inevitably they describe every other Sunni faction as deviated from the true Sunnah including each other. 3.2.4 Sunni

Arab Movements

The roots of a whole range of different Arab and Muslim revival movements ranging from Arab socialism, secular nationalism and the Ba’ath movement, through to the Muslim Brotherhood, Salafism (literally returning to the roots) and movements to restore the Khilafat or Caliphate, can be traced back to Egypt in the 1870s. The secular movements among them have had less significance recently compared with when countries struggled for independence from colonial rule. However most of the religious-based movements have some presence among Arab-speaking communities in Britain and Europe today although the majority of Arabs in Western society are much more secular-inclined than Asian Muslims living in the West. 3.2.5 ‘Wahabbis’

In the Arabian peninsular there was a vicious struggle against Ottoman Turkish rule, culminating in the collapse of the Ottoman empire in 1924 and the formation of the state of Saudi Arabia. Detestation of any Turkish influence and the presumed corruption of Islam by external influences contributed to the formation of a very narrow definition of Sunni Islamic orthodoxy by the Saudis, commonly known as ‘Wahabbi-ism’ after its formulator in the 18th century, although the term Wahabbi-ism is resented and is usually used disparagingly against the Saudis and against many other groups sceptical of mystical practices in Islam. 3.2.6 Abul

A’ala Maudoodi

Arab

Muslim revival movements also stimulated similar political-oriented Muslim

groups in the Indian sub-continent in the first half of the 20th century, in particular

Jamaat Islami led by Maudoodi in

Pakistan. This organisation plays a major role in Pakistani politics

and Maudoodi's work inspires a cluster of

influential organisations including UK Islamic Mission and the Islamic

Foundation in Leicester. (Such bodies prefer the title 'Islamic

Movement' to descibe themselves, though this is not

in common usage and sounds a little too generic.) Although their

Islamic practice is almost indistinguishable from Deobandis and Bareilvis, they are far more inclined towards mainstream

political activism than either of these more tradition-bound factions.

They influence the main protagonists of the Muslim Council of Britain,

although the MCB strives earnestly to be non-partisan. 3.2.7 Salafi

Since

the 1980s there has been an increasing awareness among Western Muslim

youth of their identities as Muslims as distinct from their ethnic

identities, which have become diffused in younger generations. As

specifically Muslim issues have become topical, these have focussed

youngsters’ attention on Islam. At the same time, these generations

have an inability to connect with the obscure factionalism of their

parents, and they have available to them high quality literature in

Western European languages that challenges conventional Islamic

authority and propagates concepts about returning to the roots of Islam,

the Salaf. These influences have combined to produce an

influential and growing body of young Muslims who have adopted a spectrum of

practices ranging widely from militant hostility to full participation in

Western society, and coming under a broad umbrella generally known as

Salafi-ism. Its relative accessibility also makes it attractive to many

converts to Islam. 3.2.8 Extremists

It is vital to recognise that association with specific factions does not indicate inclination towards politically motivated violence – the few Muslims who have been implicated in violence of this kind have had a variety of religious and other influences including from mainstream Muslim groups – and conversely some of the most outspoken and challenging groups include members who are directly contribute to work to maintain the law and counter political violence. It is also important to recognise and discount the fact

that Muslim spokesmen may label groups as extremist or militant through

ignorance or prejudice or due to antagonism between factions and even basic

misunderstanding of what particular groups stand for. Similar ignorance

exists among writers, journalists and other commentators outside the

Muslim community who have often misconstrued derogatory claims about groups

and individuals. There are very few dependable texts on the subject.

Understanding and tackling extremism is a complex process. If it

is thought to be an issue then expert help is strongly advised. 3.2.9

Factions and Fringe Movements

As is inevitable with any system of belief, individual adherents to different factions have different thresholds of tolerance of dissenters from their faction. Willingness to accept and work with other Muslims varies considerably, and community initiatives may break down because of factional rivalries, e.g. if one group predominates in an initiative, others may ignore the initiative or hinder it or lobby against it. 3.2.9.1 Ahmadiyya

and Nation of Islam

Over the centuries, groups have sprung up in different parts of the Muslim world that have had major differences with mainstream Islam. Some have disappeared again into obscurity; others such as the Baha’is and even the Sikhs, have explicitly parted company with Islam after a while. There is uniform agreement among all Muslims that two sects are entirely outside Islam although the two describe themselves as Muslims. One group is Ahmadiyya, which started in what is now Pakistan, but now has its world headquarters in Morden, south west London. Its followers are often described as Qadianis. The other is the American black separatist movement, Nation of Islam. Both sects have claims about prophethood, allegedly vested in Ghulam Mirza Ahmed of Qadian, and Elijah Muhammad respectively, that contradict fundamental tenets of Islam. Any attempt to put together a Muslim community activity that depends critically on either of these groups’ participation is likely to meet very serious objections. Brixton Mosque is a focal point of Afro-Caribbean converts to Islam, but has no connection with Nation of Islam. Qadianis often portray themselves as mainstream Muslims to gain influence among political and government organisations, but no Muslim body has any involvement with them of any kind, whereas host organisations may mistakenly believe they have succeeded in representing the Muslim community in their affairs. 3.2.9.2

Cults

Some concern has been raised about cults by policy

makers tackling extremism. The well-defined nature of Islamic doctrines

make it very difficult for any charismatic and unorthodox cults to form

without being challenged at a very early stage, and the dynamism and

interactivity between Muslims of different backgrounds, especially among the

younger generations, would quickly raise those challenges. There is no

evidence of the presence of bizarre cults at work in the Muslim community in

Britain. Whether or not research that considers extremist militant

groups as cults achieves anything useful is outside the scope of this

booklet. 3.3

Muslim Groups in Britain and in London

3.3.1

Muslims in Britain

There is no precise figure for the number of Muslims in Britain, because there can never be a precise definition of who is a Muslim from a demographic perspective. Estimates vary between 1.6 million in the 2001 UK census, to up to 2.5 million in some of the more expansive polemics. It is equally hard to define the number of masjids ("mosques") in Britain because places used for prayer range from grand, purpose-built designs to borrowed rooms or hired halls, and while some date back 30 or 40 years, and a few even longer, many exist in one place only for a few years, while they raise money to find somewhere more suitable. The vast majority are small to medium-sized houses. This website includes arguably the most accurate listing of UK masjids, at "Map of Masaajid/Mosques". In November 2008 a Parliamentary Question received this answer: "Meg Hillier: The Places of Worship Registration Act 1855 provides for places of religious worship, except those of the established Church, to be certified to the Registrar General. A building has to be certified as a place of religious worship before it can be registered for marriages by the Registrar General under the Marriage Act 1949. ... The total number of buildings currently recorded by the Registrar General as certified places of meeting for religious worship by those professing the Muslim religion in England and Wales is 809. Of those 159 buildings are registered for marriage." Clearly the difference between the 800 or so referenced here and the doubled number in my list indicates that half of the premises used are not formally registered as places of worship, which in part is due to avoidance of planning procedures, but part simply down to the informal and transient nature of many masjid and madressah arrangements, even when they persist for many years. At least 96% of Muslims in Britain, and approximately 1520 or 96% of masjids or mosques, are Sunni, and about 2% are Shi’a, with 67 masjids. The majority of Sunni masjids broadly follow the principles of Deoband Madressah (circa 700-800 masjids) and about 350 others those of Bareilli Madressah. About 60 are Maudoodi-influenced and about 60 Asian-run masjids adhere to Salafi or similar principles.[1] Of the remainder, approximately 12 are very large institutions with very substantial numbers of Arab-speaking worshippers, and another 20 or so are very small and makeshift Arab-run masjids. 12 are Turkish-language, 5 are run by Nigerians, 1 each by Indonesians, Malays and Brunei-ese, 3 by Guyanese and 5 by Iranians, 1 mainly by white converts and 1 is a vital resource for black converts. Most universities have campus prayer rooms dedicated to university Muslim society members’ use, supported from university union funds and led and managed as masjids by students. Given the small numbers of Shi’as and Shi’a masjids,

many Shias will use Sunni masjids, although the reverse is rarely true.

Otherwise most Sunnis will use whichever masjid is convenient. The

religious differences between the Deobandi, Bareilvi and

Maudoodi-ist Sunni factions are subtle and

very obscure, and in Britain only the most partisan followers of each

will make a principle of boycotting the others’ masjids. Indeed, most

Muslims and most masjid committees downplay sectarian allegiances and

many have insufficient knowledge even to be aware of the differences.

However communities also tend to split into ethnically separate Gujerati, Pakistani and Bangladeshi masjids

(although this too is always downplayed), subdividing into factional lines as

well, so when engaging with the Muslim community it is important to make

sure that the right coverage is achieved, therefore it is important to

recognise the obstacles posed by factionalism and ethnic divisions. 3.3.2

Muslims in London

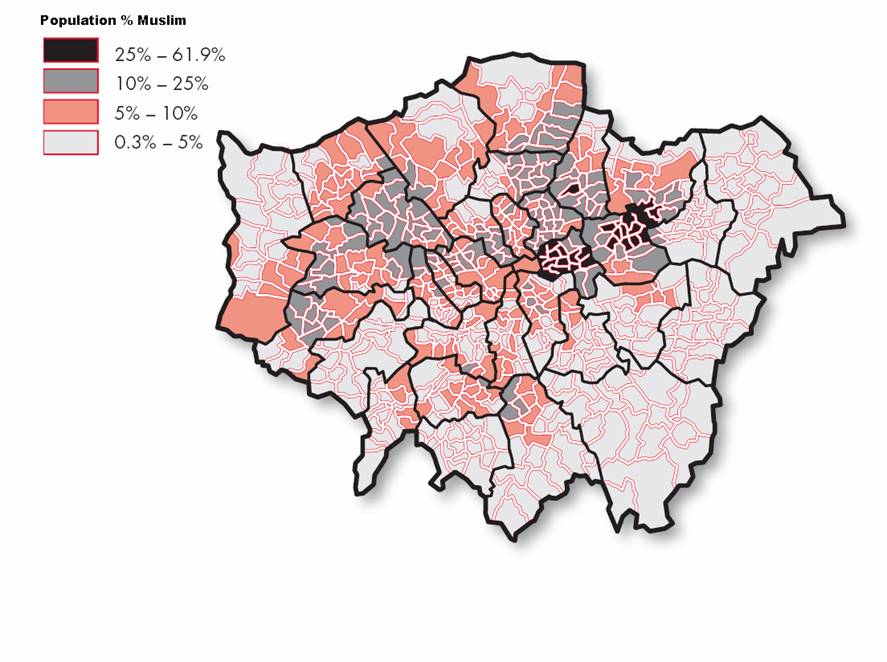

Using data derived from the 2001 Census, The Guardian deduced that “London's Muslim population of 607,083 people is probably the most diverse anywhere in the world, besides Mecca.” Even the Meccan comparison is questionable, since residential and economic conditions are quite peculiar there.

Source: 2021 Census, National

Statistics website: www.statistics.gov.uk

Source: the author.[1] Most of the smaller ethnic communities among Muslims in Britain are to be found in London. Thus 4 masjids in London are Turkish-language, 2 are run by Nigerians, 1 each by Indonesians, Malays and Brunei-ese, 3 by Guyanese and a couple by Iranians and 1 by black converts. Noting the total rejection of Qadianism from Islam by all except themselves, nevertheless the Qadiani/Ahmadiyya presence is significant, since Morden in south west London is their world headquarters. The majority of Qadiani practitioners are in south west London, and they have 8 meeting halls with total capacity of 12,100 and approximately 25,000 followers in London. As explained in the previous section, it is important to consider the various Muslim factions when pursuing activity concerned with engagement with Muslim community organisations, because activity that perhaps unwittingly focuses on one faction or ethnic group within Islam may drive others away.

Ethnic groups in London are reasonably well recognised by most government bodies, but difficulties arise when ethnic identities are accorded more significance than religious affiliation and factionalism within religions. The main countries of origin among Muslims in London are Bangladesh, Pakistan and India, followed by Turkey/Cyprus, Algeria, Morocco, sub-Saharan West Africa, the Sahel or Horn of Africa, Egypt, Indonesia/Malaysia/Singapore. This breakdown illustrates some of the problems in ensuring comprehensive representation. For example Muslims are a minority in India, but in Britain Indian Muslims are approximately equal in number to Hindus. However for example there are huge ethnic and cultural differences between Gujerati and Tamil Indian Muslims or Indian Muslims from Guyana, all of whom are present in London. The Deobandi, Bareilvi and Maudoodi-ist Sunni factions represent to some degree the older generation of south Asian Muslims, Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, if not explicitly then at least by inclination. The younger generation often disdains these traditional factions and the barriers the factions set up, and they also resent the strong ethnic divisions of their elders. These are among the factors that turn many youth away from the mainstream Muslim community to seek more radical alternatives. However this disdain often creates further factions and new ‘breakaway’ masjids, in particular those following Salafi ideas.

[1] Few masjids claim explicit allegiance to particular factions and indeed most masjids are utilised by all in the neighbourhood. Nevertheless most masjids have very clear indications of the factions their managements approve of - the same managements are invariably vigorous in obstructing activites of the factions of which they most strongly disapprove. The numbers are derived from first hand knowledge of the masjids or more subtle indicators of the organisers’ allegiances. In some casesorganisations with clear affiliations have published lists of masjids who are directly affiliated or whose ethos shares their outlook. These numbers vary not only as new masjids are opened, but also as masjid management committees change between factions. Discrepancies between the figures and their totals arise because of overlaps as well as absences. e.g. Many Arabs pursue Salafi practices, and many Salafis practice in mainstream masjids. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||